From an article in the Sacramento Bee on June 16, 2018.

PUNTA GORDA

PUNTA GORDA

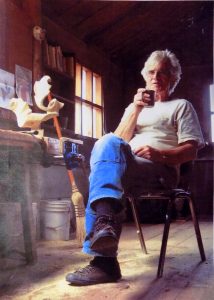

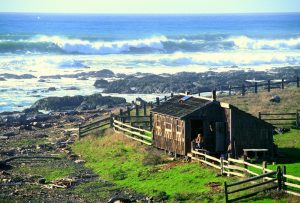

Sculptor John McAbery lives here in a one-room cabin about as far off the grid as one can imagine – on a rugged stretch of the Lost Coast with no electricity or phone or any other ties to civilization save a solar-powered radio.

That’s just how the 73-year-old artist likes it. “No distractions,'” he says of his monastic hideaway in Humboldt County. Plus, the picturesque setting offers plenty of inspiration for the graceful, ribbon-like wood sculptures he’s been turning out for the past 25 years.

From his work table, he can look out on his own stretch of windswept beach, just a short walk to the Punta Gorda Lighthouse to the south, and see elephant seals, herons, pelicans, porpoises and, often in the distance, gray, blue and humpback whales.

“I’m just inspired by the magic of this place, all the energy and movement,” he said recently as he showed a couple of visitors around his 25-acre spread, accessible only by a 4-wheel-drive vehicle. “If I didn’t live out here, I probably wouldn’t be doing what I’m going.”

McAbery, who is having his first Sacramento-area show starting June 21 at the Ellu Gallery in Grass Valley, has been called a “zen master” of wood – a reference in part to his astonishingly original and painstaking methodology.

McAbery, who is having his first Sacramento-area show starting June 21 at the Ellu Gallery in Grass Valley, has been called a “zen master” of wood – a reference in part to his astonishingly original and painstaking methodology.

Instead of steaming pre-cut strips of wood and bending them into desired shapes – as most sculptors would do – McAbery carves intricate three-dimensional works, full of delicate, intersecting coils, from single 80-pound blocks of California bay laurel wood that he harvests from fallen trees near his home.

“When you consider how challenging and complex that is, it’s hard to really grasp how he does it without destroying every piece of wood,” says Ryan McVay, an artist who runs the Ellu Gallery. Equally surprising: McAbery does all his work with hand tools – Japanese keyhole saws, gouges, a cheese-grater-like rasp called a microplane and, for the final steps, lots and lots of sandpaper.

McAbery, who typically spends 120 hours or more on a single piece, says he’s not sure he could do his work with power tools even if he had electricity. Regardless, he wouldn’t consider it. “The noise would drive me crazy,” he says, interrupting the meditative state he says he enters when carving.

McAbery, who typically spends 120 hours or more on a single piece, says he’s not sure he could do his work with power tools even if he had electricity. Regardless, he wouldn’t consider it. “The noise would drive me crazy,” he says, interrupting the meditative state he says he enters when carving.

His works – which go for $1,500 to $5,000 – have been shown in big galleries in Los Angeles, Carmel, Aspen, Seattle, Santa Fe and elsewhere, but in recent years McAbery has focused on selling exclusively from his website. The Grass Valley show represents a renewed effort to give the work a wider audience.

McAbery traces his evolution as an artist to a winter morning in 1992, a day off from the plumbing and construction work he was doing then in the town of Petrolia, 45 minutes down the coast. He was walking on his beach and saw a piece of mahogany driftwood that resembled a foot. He took it home and, using a bent and sharpened screwdriver, carved it into a spoon.

“I was hooked,” he said of that first project. “I probably made 100 spoons.” Then he moved on to carving pieces that resembled abalone and other sea shells. Inspired he tried something harder: a twisting mobius strip. The first 15 tries ended up as fuel for his wood-fired stove but he finally got it right and ever more intricate pieces have followed, many of them designed by Gretchen Bunker, a fellow artist who trekked by McAbery’s home one day in 1994 and ended up being his life partner.

“I was hooked,” he said of that first project. “I probably made 100 spoons.” Then he moved on to carving pieces that resembled abalone and other sea shells. Inspired he tried something harder: a twisting mobius strip. The first 15 tries ended up as fuel for his wood-fired stove but he finally got it right and ever more intricate pieces have followed, many of them designed by Gretchen Bunker, a fellow artist who trekked by McAbery’s home one day in 1994 and ended up being his life partner.

(“I’m his fiancee,” she clarified, smiling. “He asked me to marry him 21 years ago. I said ‘yes.’ We just haven’t gotten around to it.”)

Until Bunker came along, McAbery considered carving more a hobby than a potential occupation. But she convinced him to start selling a few pieces and an “accidental” career was born. “One day I was plumbing. The next I was an artist,” he said.

For all his years of work and mastery, McAbery still ends up producing some gorgeous pieces of firewood. That will happen when you’re making sculptures so delicate that they tremble, like bobbleheads, when lifted. A current project – an especially complex commission piece – had to be restarted from scratch four times; the first three attempts were thwarted when McAbery ran into “blind” knots that were invisible until he got deep into the wood.

But that’s just part of the process and perhaps a part of the zen quality of McAbery’s work: peeling back layers of wood, unsure of what will be revealed beneath the surface but learning something from the journey regardless.

“It’s all a matter of challenging myself, pushing limits and not worrying about mistakes,” he said.

The same might be said of McAbery’s journey to this remote spot he calls “the end of the continent.” He visited here once when he was 18, then returned with his two young kids in his mid-30s and bought his property from a rancher. Earlier, he had lived in Monterey, Colorado and Idaho, working in construction and, for a time, making sheepskin coats.

The same might be said of McAbery’s journey to this remote spot he calls “the end of the continent.” He visited here once when he was 18, then returned with his two young kids in his mid-30s and bought his property from a rancher. Earlier, he had lived in Monterey, Colorado and Idaho, working in construction and, for a time, making sheepskin coats.

He continued to do construction and plumbing after moving here while operating a restaurant called “The Hideaway” in Petrolia, an unincorporated town of about 400 people. But McAbery said he didn’t really find fulfillment until he discovered that piece of driftwood one day and turned it into a spoon.

“I feel like I have an angel on my shoulders,” he said of the events that brought him here and made him an artist. “I’ve done lots of things. But this was the first thing where I thought, ‘This is me.'”